www.hikingclub.ca

July 2010 West Coast Trail photos (Part 4 of 4) by Andrew

Our day of rest at Tsusiat

My gathering of prime firewood for the midnight campfire

The stage is set for when the curtain rises after sunset

The naked group skinny-dipping photos withheld pending model release forms being signed

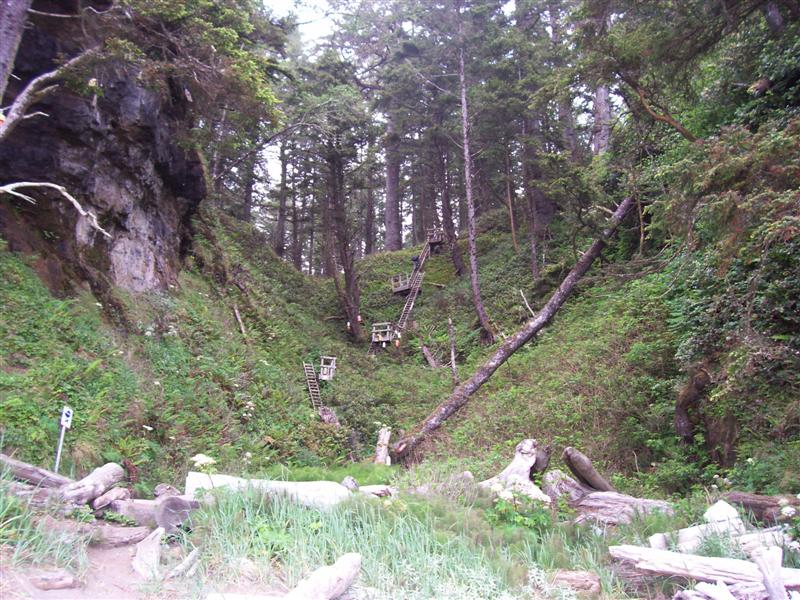

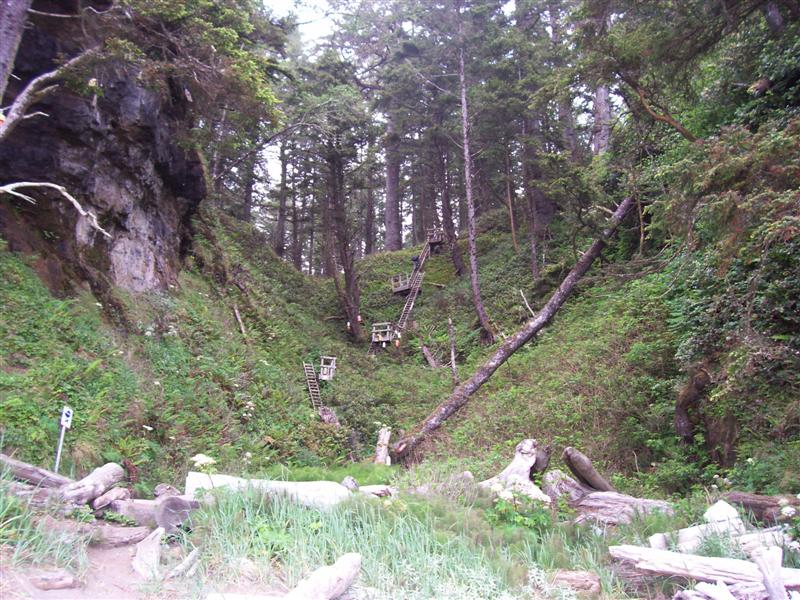

Believe it or not this is the 'entrance' to the bearbox and outhouse area

and this is actually better than our last trip where it was cut off at high tide

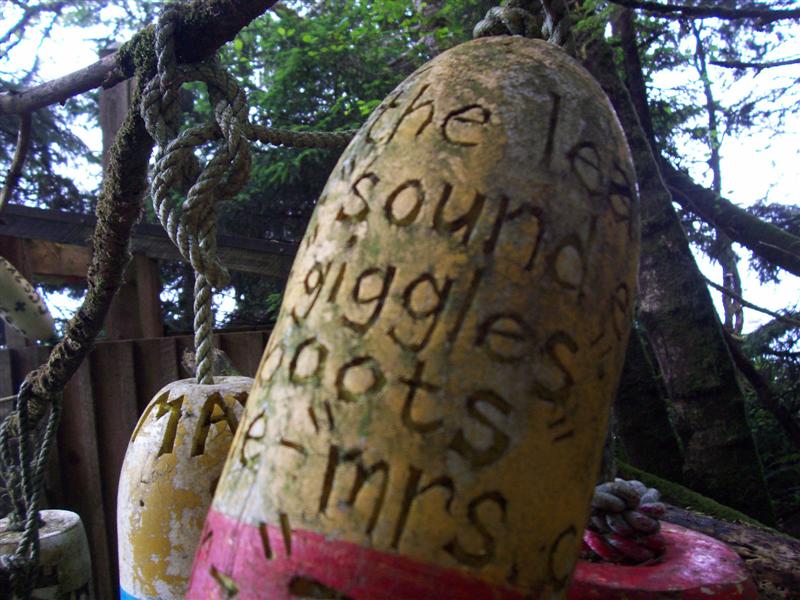

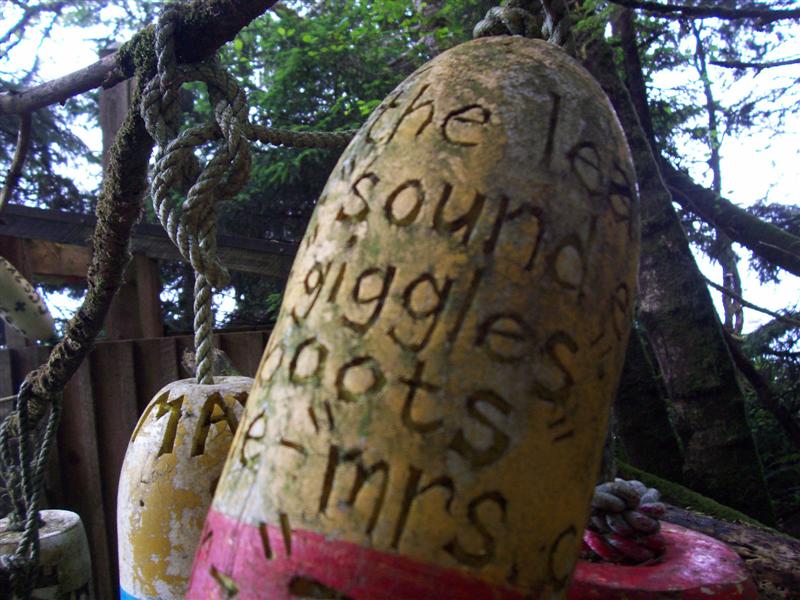

Our carved floats from our 2005 WCT trip still hanging

Night falls and the morning people are long gone hidden inside their tents,

even the night people disapear into their sleeping bags leaving me alone on the beach

It has been said that there is a wrecked ship for every mile of

coast along the Graveyard of the Pacific.

The Graveyard of the Pacific is a nickname for a stretch of the coastal region

in the Pacific Northwest, from Tillamook Bay on the Oregon Coast northward to

the tip of Vancouver Island.

The region's seas are frequently subject to

heavy and unpredictable weather year round combined with the rugged, largely

undeveloped coastline, especially along Vancouver Island and its northwestern

tip at Cape Scott, causing sea conditions which endanger many marine vessels.

More than 2000 vessels and 700 lives have been lost near the Columbia Bar,

and 484 additional wrecks at the south and west sides of Vancouver Island.

Some of them are working tugs or lumber barges, some are freighters.

There are Canadian and foreign vessels, war ships and passenger ferries.

The ocean does not distinguish between them.

Shipwrecks of the past and present are all the result of a number of factors

that combined to cause disaster. Ignorance of the local geography, a tired and

overworked crew, a vessel unfit to sail, surprise winds and greedy shipping agents

who overload on cargo have all contributed to the wreck of ships and the loss of

lives off the Vancouver Island coast.

The SS Valencia was an iron-hulled passenger steamer wrecked off the coast of

Vancouver Island, British Columbia in 1906. Built in 1882 by William Cramp and Sons,

she was a 1,598 ton vessel, 252 feet (77 m) in length.

Some consider the wreck of the Valencia to be the worst maritime disaster on the

southwest coast of Vancouver Island, an area so treacherous it was known to mariners

as the Graveyard of the Pacific.

The Valencia normally served the California–Alaska route. She was not equipped

with a double bottom and, like other early iron steamers, her hull compartmentalization

was primitive.

In January 1906, however, she was temporarily diverted to the San Francisco–Seattle

route to take over from the SS City of Puebla, which was undergoing repairs in San Francisco.

The weather in San Francisco was clear, and the Valencia set off on January 20 at 11:20 AM

with nine officers, 56 crew members and at least 108 passengers aboard.

As she passed by Cape Mendocino in the early morning hours of January 21, the weather

took a turn for the worse. Visibility was low and a strong wind started to blow from

the southeast.

Unable to make celestial observations, the ship's crew was forced to rely on dead reckoning

to determine their position. Out of sight of land, and with strong winds and currents,

the Valencia overshot the entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca by more than 20 miles

(30 km).

Shortly before midnight on January 22, she struck a reef near Pachena Point on

the southwest coast of Vancouver Island.

Immediately after the collision, the captain ordered her engines reversed. As soon as

she was clear of the rocks, crew members reported a large gash in the hull into which

water was pouring rapidly.

To prevent her from sinking, the captain ordered her run aground,

and she was driven into the rocks again. She was left stranded in sight of the shore,

separated from it by 50 metres of heavy surf.

In the ensuing confusion, six of the ship's seven lifeboats were lowered into the water

against the captain's orders, all of them improperly manned. Three flipped while being

lowered, spilling their occupants into the ocean; of the three that were successfully

launched, two capsized and one disappeared.

The scene at the wreck was horrific, as

one of the few survivors, Chief Freight Clerk Frank Lehn recounted:

“ Screams of women and children mingled in an awful chorus with the shrieking of

the wind, the dash of rain, and the roar of the breakers. As the passengers rushed

on deck they were carried away in bunches by the huge waves that seemed as high as

the ship's mastheads. The ship began to break up almost at once and the women and

children were lashed to the rigging above the reach of the sea. It was a pitiful

sight to see frail women, wearing only night dresses, with bare feet on the freezing

ratlines, trying to shield children in their arms from the icy wind and rain. ”

Only 12 men made it to shore, and of those three were washed away by the waves after

landing. The remaining nine men scaled the cliffs and found a telegraph line strung

between the trees. They followed the line through thick forest until they came upon a

lineman's cabin, from which they were able to summon help.

These nine men, who became known as the 'Bunker' Party, after the survivor Frank Bunker,

eventually received much criticism for not attempting to reach the top of the nearby cliff,

where they might have received and made fast, the cable fired from the Lyle gun on board

the Valencia.

Meanwhile, the ship's boatswain and a crew of volunteers had been lowered in the last

remaining lifeboat with instructions to find a safe landing place and return to the

cliffs to receive a lifeline from the ship.

Upon landing, they discovered a trail and a sign reading "Three miles to Cape Beale."

Abandoning the original plan, they decided to head toward the lighthouse on the cape,

where they arrived after 2 ˝ hours of hiking.

The lighthouse keeper phoned Bamfield to report the wreck, but the news had already

arrived and been passed on to Victoria. This last group of survivors was "well-nigh

crazed" by their last sight of the remaining stranded passengers.

“ the brave faces looking at them over the broken rail of a wreck and of the echo of that

great hymn sung by the women who, looking death smilingly in the face, were able in the

fog and mist and flying spray to remember: Nearer, My God, to thee. ”

Once word of the disaster reached Victoria, three ships were dispatched to rescue the

survivors. The largest was the passenger liner SS Queen; accompanying her were the

salvage steamer Salvor and the tug Czar.

Another steamship, the SS City of Topeka, was later sent from Seattle with a doctor,

nurses, medical supplies, members of the press, and a group of experienced seamen.

On the morning of January 24, the Queen arrived at the site of the wreck, but was unable

to approach due to the severity of the weather and lack of depth charts.

Seeing that it would not be possible to approach the wreck from the sea, the Salvor

and Czar set off to Bamfield to arrange for an overland rescue party.

Upon seeing the Queen, the Valencia's crew launched the ship's two remaining life rafts,

but the majority of the passengers decided to remain on the ship, presumably believing

that a rescue party would soon arrive.

Approximately one hour later, the City of Topeka arrived and, like the Queen, was unable

to approach the wreck.

The Topeka cruised the waters off the coast for several hours searching for survivors,

and eventually came upon one of the life rafts carrying 18 men. No other survivors were

found, and at dark the captain of the Topeka called off the search.

The second life raft eventually drifted ashore on an island in Barkley Sound, where the

four survivors were found by the island's First Nations and taken to a village near Ucluelet.

When the overland party arrived at the cliffs above the site of the wreck, they found

dozens of passengers clinging to the rigging and the few unsubmerged parts of the Valencia's

hull.

Without any remaining lifelines, however, they could do nothing to help the survivors,

and within hours a large wave washed the wreckage off the rocks and into the ocean. Every

remaining passenger drowned.

Estimates of the number of lives lost in the disaster vary widely; some sources list it

at 117, while others claim it was as high as 181. According to the federal report, the

official death toll was 136 persons. Only 37 men survived, and every woman and child

on the Valencia died in the disaster.

Five months after the incident, a local fisherman claimed to have seen a lifeboat

with eight skeletons in a nearby sea cave, but the party dispatched to investigate

was unable to locate the cave.

In 1910, the Seattle Times reported that sailors claimed to have seen a phantom ship

resembling the Valencia near Pachena Point. In 1933, 27 years after the disaster, the Valencia's lifeboat #5 was found floating

in Barkley Sound. Remarkably, it was in good condition, with much of the original

paint remaining.

The ladders back to the trail northward for the escape from Tsusiat

The remains of an orginal linesmen cabin from 100 years ago

The boiler from the steamship 'Michigan'

A Steller Sea Lion and his harem

Pachena Bay and our ride back to civilization

|